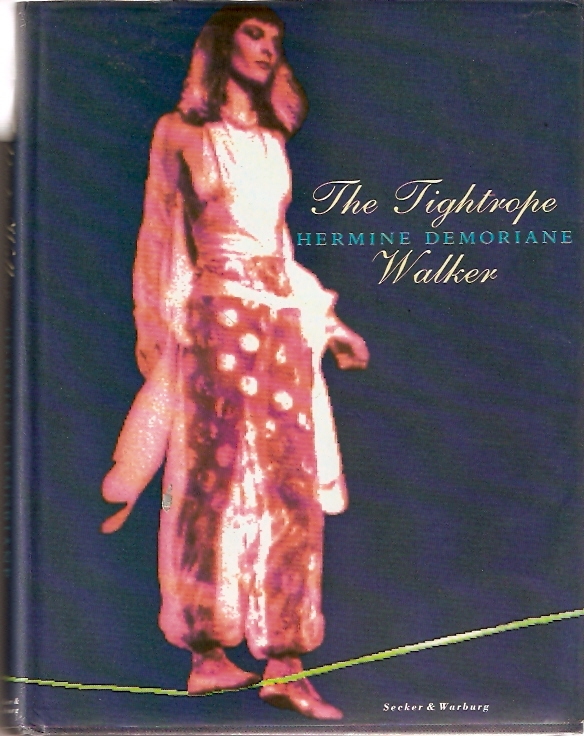

TightRope Walker & Author,

Author of “The Tightrope Walker”

to The Blondin Memorial Trust, 3 Raleigh Street, London Nl 8NW

The ancient Greeks had four different words for rope-walkers:

the Oribat dances on the rope,

the Neurobat sets his rope at great heights,

the Schoenobat flies down the rope and

the Acrobat does acrobatics on the rope.

In 260 BC Censor Messala did away with these distinctions, uniting them in a single word:

funambulus [funambule]

[from funis, a rope, and ambulare, to walk.]

Ancient Greek funambules

In Ancient Greece, together with members of the Senate, rope-walkers wore white. This indicated that they required the special protection of the Gods. The ancient Greeks were fascinated by tightrope-walking, which seemed to owe more to magic than technique. But its very ‘fascination’ excluded it from the Olympics and other public games. Thus the rope-walker was assimilated into the ranks of performers rather than gymnasts, and classified under a specialised section of the Games. According to Alexander of Alexandria, a special prize, ‘The Thaumatron’, was created for them and awarded to ‘anyone who shows people something amazing, out of the ordinary’.

In ancient Rome, reports Capitolinus, Marcus Aurelius ordered that mattresses should always be put underneath the ropes after a little boy rope-dancer fell at one of his celebrations. Roman tightropes must have been high, but not so high as to make precautions futile.

Neither in Greece nor Rome were rope-walkers admitted to the Games. ’Their activity’, writes Pausanias, ‘didn’t improve the body or the mind, and could only be called violent and life-endangering’. It was all right for them to appear at celebrations and other triumphs, but they were denied licence to compete amongst themselves at public games.

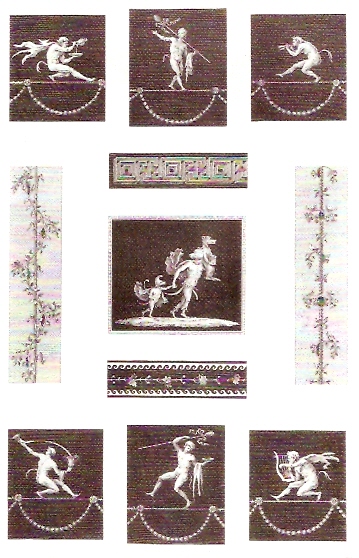

Aquatint by P. Choffard, C 1804, after the frescoes at Herculaneum, showing six funambules

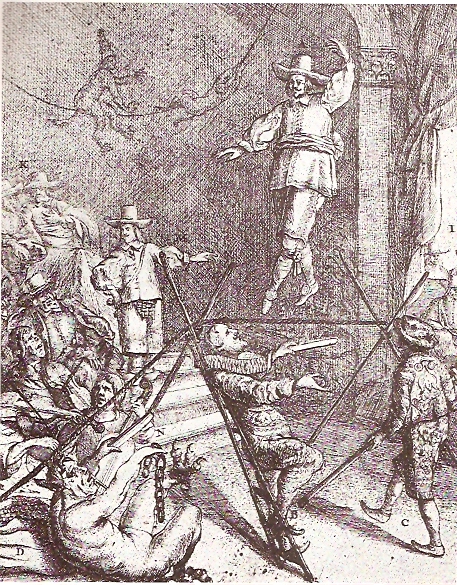

As the rope-dancers became alienated from the Roman world of sport and athletics, they join a group of mountebanks, the Archimomons. Under the influence of this group, they supplement their show with satire, attacking the moral betrayals of politics and society with grotesque caricatures of its nuptial dances. They would never have dared to do so in Greece, where the art of rope-walking was held in the highest regard as part of the education of the young.

The tightrope-walkers find themselves at odds with new-born Christianity. Hell-bent on daring, they set up their ropes at incredible heights, beyond the salvation of mattress or net. St John Chrysostom describes how ‘They could barely walk up and down on them, a blink of an eye or any loss in concentration would have been enough to consign them to the dust.’ Moreover, a few tightrope-walkers are trying to pull the stunts of the rope-dancers at such heights: ‘They undress’, writes St John, ‘and then get dressed again, as though they had just got out of bed. Some of the audience daren’t watch out of modesty, others out of fear.’

Between the fear of some and the morals of others begins a long battle.

‘Then that came to pass which silenced every mouth and fixed every eye. For in the meantime the Rope-Dancer had begun his task: he had stepped forth from a little door and walked upon the rope which was stretched between two towers so that it spanned the market-place and the people. When he was midway the little door opened and a gaily dressed fellow like a clown leaped out and went with quick steps after the first. “On with you, lame-leg,” he cried in a terrible voice. “On with you, lazy-bones, cheat, sallow-face! - lest I tickle thee with my feet! What dost thou here between the towers? Thy place is in the tower. Thou shouldst be jailed, for thou barred free way to thy better!” And at each word the clown drew nearer and nearer; but when he was but one step behind, there happened that terrible thing which silenced every mouth and fixed every eye; for uttering a cry like a devil, he leaped over him that barred his way, who, seeing his rival’s triumph, lost both his head and his footing on the rope, threw aside his wand, and himself shot down yet faster with arms and legs whirling. The market place and the crowd became as a storm-tossed sea: every man fled stumbling over his neighbour, and chiefly there where the body was about to strike the ground.

Zarathustra, however, kept his place, and the body fell close beside him, badly disfigured and broken, but not yet dead. After a while consciousness returned to the injured man, and he saw Zarathustra kneeling beside him. “What dost thou do there?” he asked at last. “I knew long since that the devil would trip me. Now he draggeth me into hell: will thou prevent him?”

“By my honour, friend,” answered Zarathustra, “That which thou speakest doth not exist: there is no devil and no hell. Thou soul will be dead even sooner than thou body: henceforward fear nothing more.”

The man looked up distrustfully: “If thou speakest truth,” he said, “losing my life I lose naught. I am little more than a beast, taught to dance by blows and titbits.”

“Not so,” said Zarathustra, “Thou had made danger thy calling, there is naught contemptible in that. Now thou diest by thy calling; therefore will I bury thee with mine own hands.”

When Zarathustra had spoken thus the dying man made no answer, but moved his hand though he sought Zarathustra’s, to thank him.’ [Friedrich Nietzsche, “Thus Spake Zarathustra”, 1883-92]

’Ita populus studio stupidus, in funambulo animum occuparat… ’ Our spectators were distracted by rope-walkers, said Terence, writing about what happened at the first performance of his play “Hecyria”, in AD 333, when a troupe of funambules was rumoured to have arrived in town).

‘Go thou, tightrope walker, in sanctity and innocence, like the fair sex itself, whose beautiful discipline can propel you on a super-thin thread, balancing flesh with spirit, ruling the soul with faith, checking the eye with fear.’ [Tertullian, “De Pudicitia”, 464]

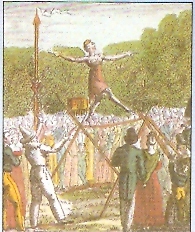

As in every other great cult, religion and commerce are inextricably linked. All hostilities are suspended during fairs, which is why religious celebrations and assemblies of states are fixed upon their dates. The first fairs in Great Britain, Stourbridge and Bartholomew, date from the Roman invasions.

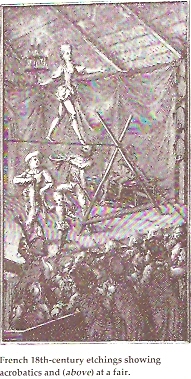

The fair is where the rope-walkers makes his living, using his own jacks to lift the anchored rope some twelve feet into the air. He puts up a curtain all around, and one has to pay to get inside the enclosure. Or else he performs high above the fair, sponsored by the knowing merchants as advance publicity. He may also attach himself to bear-tamers and contortionists, quacks and con-men.

“It is here, in the market place, that he meets his people, fellow rope-walkers who have come from abroad with the merchants of emeralds and pearls, fine linen, coral and agate.

In the first centuries of Christendom, ‘the first fairs were formed by the gathering of worshippers and pilgrims in sacred places, and especially within or about the walls of abbeys and cathedrals on the Feast days of the Saints enshrined therein’. [Morley, “Memoirs of Bartholomew Fair”, 1892]

After the feast, the King starts ruling, the princess bears children and the rope-dancer goes back to the fair, where he was found in the first place.

And so is the rope-dancer, who must practice in the blaze and din of the fair, until the next feast day. The fair is his condition, as the ashes are Cinderella’s.

During the fifth century in France, a series of Councils of Bishops attacks the mountebanks’ companies as though they are the very embodiment of evil on earth. In 549 the Châlon Council forbids them to come near the Church’s property, virtually putting a ban on the ‘profane’ art of rope-walking, since it was then practiced exclusively at markets and fairs, which were always held near the Church, if not in the churchyard itself.

In 554 Childbert, King of the Francs, forbids the clerics to watch the mountebanks, whom he groups insultingly under the name of ‘thymelici’ (drunken layabouts). Non-titurgical music is considered evil. The reputation the clerics are getting for lechery, indolence and petty theft is thought dangerously similar to that of the dread mountebank himself.

The poet Manilius suggests that those born under Pisces make good tightrope-walkers. ‘If perchance his mind is moved to consider a profession, he will be inspired with enthusiasm for risky callings, with danger the price for which he will sell his talents; daring narrow steps on a path without thickness he will plant firm feet on a sloping tightrope; then, as he attempts an upward route to heaven, he will repeatedly slide back from footholds newly gained and, suspended in mid-air, keep a multitude in suspense upon himself.’ [“De Astronomica V”, 638-660]

At Easter in medieval times, a dancer performed on a giant globe inside the church of Auxerre.

In France, further Councils, (Tours in 813, Paris in 829 and Rheims in 858), rule out any form of entertainment for the clerics. Such measures set the rope-walkers apart from society, making of him a stranger or ‘Turk’.

Phillippe-Auguste (1165-1223) kicks Mountebanks out of the [French] Court where for centuries they have been welcome. As in Rome when Tiberius banished the funambules from the city, licence is granted and withdrawn by the same power.

A man from Genoa slid, singing, down a rope stretched from Notre-Dame [Paris, France] to the Pont Saint-Michel over which the future Queen was due to pass… The bridge was covered with blue taffeta sprinkled with gold lilies, in which a slit had been made. And, as the Queen Isabeau (1371-1435) came onto the bridge, the man from Genoa entered, placed a crown on the future Queen’s head, and walked away on the rope into the falling night carrying in his hands two torches which could be seen for miles around. Some villagers thought an angel had come down from Paradise to welcome the new Queen. Others thought it was a meteor, the sign of a great event.’

‘One crosses rivers even more often [than swimming] with leather drums attached to the feet… Obviously one needs courage to do this, as in rope walking, as well as practice and great bodily strength; if one has lightness as well, the spectacle will be more beautiful and delightful.’ [Hieronymus Cardanus, “De Subtilitate”, 1556]

In 1556 Hieronymus Cardanus writes in “De Subtilitate”: Those who dance on the rope, who call themselves Funambuli, are the most daring of all men, taming the laws of nature with artiface. Indeed rope-dancing has its origins in natural magic. For the art of magic depends on natural causes and what is admirable in it comes from the occult and the hidden.

In the Middle Ages, a tightrope act was thought to be essential to give any public event its proper air of mystery. “Archeologia Britannica” describes the coronation of Edward VI (1537-1553) in 1547:

‘There was a great rope, as great as the cable of a ship, stretched from the battlements of St Paul’s [London] steeple, with a great anchor at one end, fastened a little before the Dean of Saint Paul’s house-gate; and when His Majesty approached near the same, there came a man, a stranger being a native of Aragon, lying on the rope with his head forward, casting his arms and legs abroad, running on his breast on the rope from the battlements to the ground, as if it had been an arrow out of a bow. Then he came to His Majesty, and kissed his foot; and so, after certain words to his Highness, he departed from him again, and went upwards upon the rope, till he came over the midst of the churchyard, where he, having a rope about him, played certain mysteries on the rope, as tumbling, and casting one leg from another. Then took he the rope, and tied it to the cable, and tied himself by the right leg a little space beneath the wrist of the foot, and hung by one leg a certain space, and after recovered himself again with the said rope and unknit the knot, and came down again. Which stayed His Majesty, with all the train, a good space of time.’

In Raphael Holinshed’s version, as well as sliding down the rope like the ancient Greek schoenobat, the ‘Argosine’ plaied manie pretie toies, whereat the King and the Nobles had a good pastime.’

In 1553, on the occasion of Philip of Spain’s (1527-1598) arrival in London to marry Queen Mary, there was again ‘the sight at Paules churchside, of him that came down upon a rope tied to the battlements with his head before, neither stadieng himself with hand or foot, which shortlie after cost him his life’. [Holinshed, “Chronicles”, 1577]

[In France] French Councils continue to persecute Mountebanks and Funambule: In 1560, following complaints from the Paris priests that Sunday mass is being deserted for the rope-dancers show, the Commissaire de Police de la Marre - so rightly called - confines the trouble-makers to the fairs of Saint-Germain and Saint-Laurent.

‘There was a man in Paris, in the reign of good King Charles, who could tumble and jump and do such tricks on the rope that no one today would believe had they not been witnessed at the time. He would stretch thin ropes from the towers of Notre-Dame to the Palace and on these ropes he would leap and perform such feats of agility that he seemed to be flying. Therefore he became known as ’Le Voleur’. I saw him myself as did many others. He was said to have no equal in his art, which he performed many times before the King. One day however, he missed his footing on the rope and fell from such a height that he broke all his bones. “Surely,” said the King when he learned of it, “bad luck must befall the man who presumes so much of his senses, his strength, his lightness or any other thing.”‘ Christine de Pisan, 15th Century

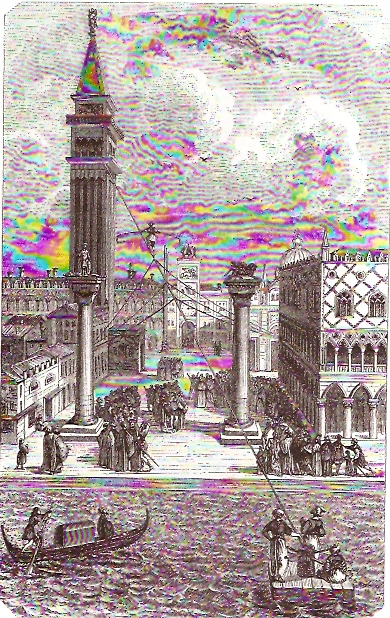

Venice had her rope-walkers who performed at least once a year before the Doge, the Senate and the foreign ambassadors on St Mark’s Day. James Peller Malcolm, in “Miscellaneous Anecdotes Illustrative of the Manners and History of Europe During the Reign of Charles II, James II, William III and Queen Anne” (1811), writes:

‘Every method has been contrived for ages to do honour to the Patron Saint of the city; and, amongst other singular customs, a man ascends and descends the tower dedicated to him on the frail support of a rope stretched from the summit, and secured at a considerable distance from the base.’

Ascending the Campanile of St Mark’s, Venice. From an engraving done

before the construction of the Sansovino Library in 1536

Having thus introduced the subject, we shall submit the following improved account of it, written in 1680: ‘Venice, March 7. The last day of the last month, the Doge, the Senate, and the Imperial Ambassador, along with above fifty thousand common spectators, beheld the solemnity of Saint Mark. In the first place, appeared certain butchers in their roastmeat clothes; one of which, with a Persian scimitar, cut off the heads of three oxen, one after the other, at one blow, to the admiration of all beholders, who had never seen the like either in this city, or in any other part of the world: but that which caused a greater wonder in the spectators was this, that a certain person, adorned in a tinsel riding habit, having a gilt helmet upon his head, and holding in his right hand a lance, in his left a helmet made of a thin piece of plate gilded, and sitting upon a white horse, with a swift pace ambled up a rope six hundred feet long, fastened from the quay to the top of St Mark’s Tower: being got half-way, his coat, which was of tinsel, happening to fall off, he made a stand, and stooping his lance submissively, saluted the Doge sitting in the Palace, and flourished the banner three times over his head.

Then, resuming his former speed, he went on and on, and, with his horse, entered the tower where the bell hangs; and presently returning on foot, he climbed up to the highest pinnacle of the tower; where sitting on the golden angel, he flourished his banner again several times, and so returning down to the tower: and there taking horse, he rode down again to the very bottom. Next year he promises to ride up to the same tower with a cart and oxen.

In the course of the Carnival, a sailor disguised as Mercury would approach the Doge upon a rope and present him with a bunch of flowers and a poem. This Mercury had a rope attached to his wings which makes the trip safe but destroys the illusion. Obviously they can’t run any risk on such an auspicious occasion. Imagine Mercury breaking his neck! That would be bad portent for Venice, and the Doge is too wise to risk it. For the Carnival is taken even more seriously than the saint’s day of the Republic’s patron saint.

A wedding, a coronation, an anniversary: at all of them the presence of a rope-walker is more than just an addition to the merry making. The rope-walker is called upon because he alone can endow an event with the necessary cosmic implications. For he is the destiny incarnate of those he honours. Today, perhaps only Neil Armstrong’s ‘giant leap for mankind’ can give an idea of the metaphorical significance of the rope-walker’s magical dance. Just as the world watched with bated breath as America’s Apollo 4 touched down on the moon, so the onlookers in St Mark’s Square knew that for a moment the fortunes of the Venetian republic rested upon the winged shoulders of their Mercury.

A King crowned, a princess married to her prince: for each the rope-walker is the symbol of their future happiness and success. Borne up by the occasion, yet holding its fate in the balance, he is there but not there: a superhuman whose movements, watched by the crowd, are ruled by forces beyond his control.

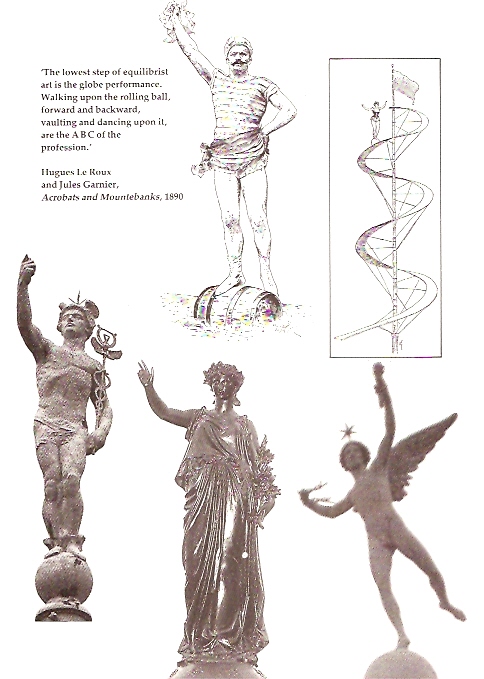

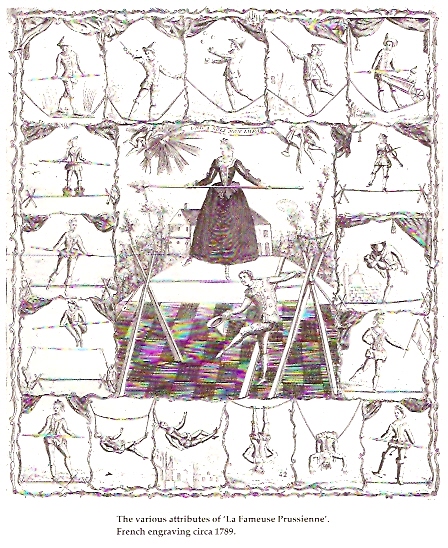

Balancing on a globe is supposed to be at the origin of tightrope walking. Jacob Spon in “Recherches Curieuses d’Antiquité” (1683) talks of balancing games on wine-filled leather drums during Bacchanalian feasts. According to him, ’any tightrope walker should be able to walk on a globe: this is fundamental technique’.

Persecution reaches its peak in England under Cromwell (1599-1658). For eighteen years, till Charles II returns, the playhouses remain closed, and the actors who challenge Parliament go to prison. Yet fencing, animal baiting, puppet shows and rope-dancing are allowed.

Caricature of Oliver Cromwell capering to the music of Guile, Deceit and Self-Interest before the English Parliament of Blood. Monkeys on a tightrope mimic him. Etching by T. Stoop c. 1653, Holland

Even though it is the Restoration, one must still have a licence to entertain. Notices go up all over town: ‘All persons concerned are hereby desired to take notice of, and to suppress, all mountebanks, rope-dancers, prize-players, ballad-singers, and such as make show of motions and strange sights, that have not a licence in red and black letters under the hand and seal of the said Charles Killigrew Esquire, Master of the Revels to His Majesty.’

The drunk going home’ is a traditional tightrope act. As long ago as the reign of Louis XIV of France (1638 - 1715), Anthony de Sceaus was imitating a drunk on the rope by walking with a series of missed steps. At the turn of the century at the Cirque d’Hiver, Aeros came on as a clochard with a bright red nose. Bottles of wine sticking out of his pockets, and he wobbled perilously on the rope without ever falling.

Mathieu de Coucy, in “Histoire de Charles VII” (1661) writes that ‘to greet the Ambassadors [of France] the Duke of Milan had a rope stretched high above his palace, 150 feet high, on which a Portugese walked backwards and forwards, saluted from his knees, sat, stood on one foot, danced to a drum, hung head downwards and did all manner of tricks till the ladies who were watching brought handkerchiefs to their eyes they were so afraid he might kill himself… ’

‘21 September 1668… And thence to Jacob Hall’s dancing on the ropes, where I saw such action as I never saw before, and mightily worth seeing: and here took acquaintance with a fellow that carried me to a tavern whither come the music of this booth, and by and by Jacob Hall himself, with whom I had a mind to speak, to hear whether he had ever any mischief by falls in his time. He told me, “Yes, many, but never to the breaking of a limb”; he seems a mighty strong man. So giving them a bottle or two of wine, I went away.’ [Samuel Pepys, 1668]

Have you seen the dancing on the rope?

When André’s wit was clean run off the score,

And Jacob’s capering tricks could do no more,

A damsel does to the ladder’s top advance,

And with two heavy buckets drags a dance;

The yawning crowd perk up to see the sight,

And slaver at the mouth for vain delight.

John Dryden (1631-1700)

The inhabitants of Charing Cross complain that rope-dancer Jacob Hall’s (1662–1681) booth attracts so many rogues to the area that they constantly lose things out of their shops. They get up a petition and a writ arrives from Whitehall. The Chief Justice tells him in court that his booth is a nuisance to the parish. As the song goes:

‘In houses of boards men walk upon cords,

An easy as squirrels crack filbords;

The cut-purses they do bite, and rob away;

But these we suppose to be ill-birds.’

Thomas D’Urfrey, “Pills to Purge Melancholy” (1719-20)

“The London Spy” (Ned [Edward] Ward) mentions a rope-walker whose ‘Tyburn locks foretold such an unhappy destiny that I was fearful of his falling, lest his hempen pedestal should have catch’d his neck. He commanded the rope to be alter’d according to his mind with such an affected lordliness that, by his imperious deportment, I perceiv’d he was master of the apes. Then, looking steadfastly in his face, I remember’d I had seen him in our town, where he had the impudence to profess himself an infallible physician. Upon this I ask’d my friend the meaning on’t’.

“Poh,” says he, “I am sorry you are so ignorant. Why, we have dancing physicians, tumbling physicians, and fools of physicians, as well as college physicians. Nay, and some of them, too, if they will, can play much stranger tricks than you are aware of. But these fellows, you must know, are bred up between death and remedy, that is the rope and the medicine, and as they grow up, if they happen to prove too heavy heel’d for rope-dancers or tumblers, they are forc’d to learn first how to be fools, and once a grown expert jack-puddings, the next degree they commence is Doctor, and leave off a painted coat and put on a plush one.”

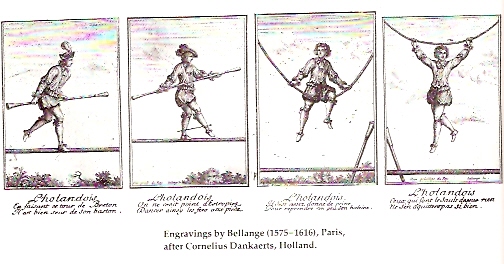

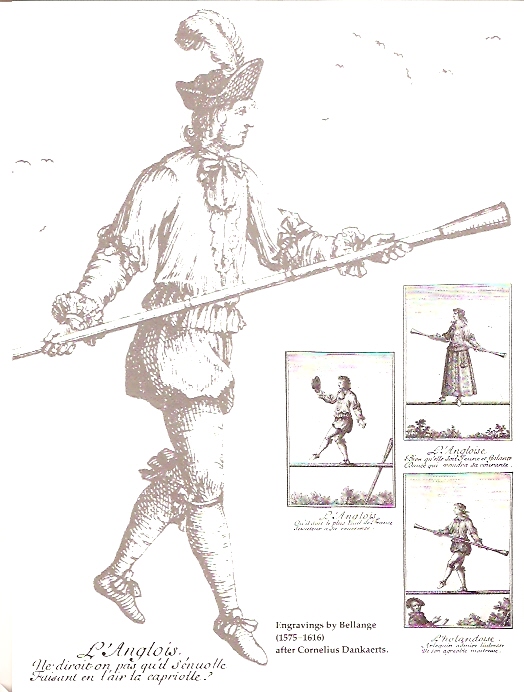

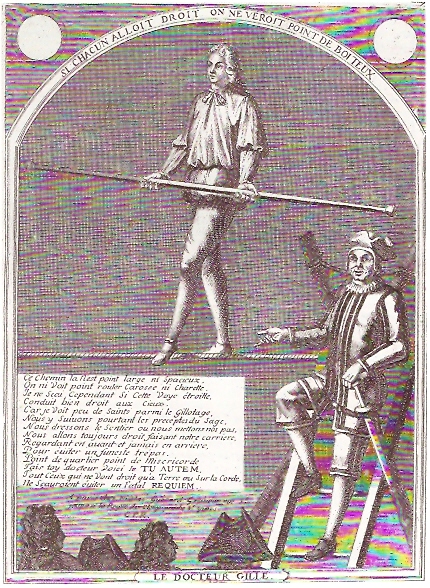

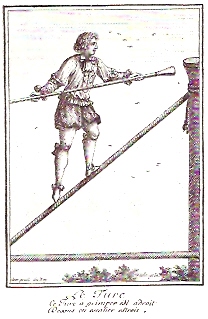

This French Doctor practices what he preaches and walks straight ahead

for a healthy life. 18th Century engraving

“The London Spy” (Edward Ward - 1698 - 1700) mentions:

‘a couple of plump-buttocked lasses, who. To show their affection to the breeches, wore’em under their petticoats, which, for decency’s sake they first danc’d in. But to show the spectators how forward a woman once warm’d is to lay aside her modesty, they doft their petticoats after a gentle breathing, and fell to capering and firking as if Old Nick had been in ‘em. These were followed by a negro woman and an Irish woman.

As soon as the black had seated herself between the cross poles that supported one end of the rope, a country fellow sitting by me fell into such an ecstasy of laughing that he cackl’d again. “Prithee, honest friend,” said I, “what dost thou see to make thyself so wonderful merry at?” “Maister,” says he, “I have oftentimes heard of the devil upon two sticks, but never zee it befovore in my life. Bezide, maister, who can forbear laughing to see the devil going to dance?”

When with much art and agility she had exercis’d her well-proportioned limbs to the great satisfaction of the spectators, the Irishwoman arose from her hempen seat to show the multitude her shapes. Her shoulders were of Atlas-build, and her buttocks, as big as two bushel loaves, shak’d as she danc’d like two quaking-puddings handing to a table in one dish. Her thighs were as fleshy as a baron of beef and so much too big for her body that they look’d as gouty as the pillars in St Pauls. Her legs were as strong as a chair-man’s, her calves being as round and hard as a football, the swelling of the muscles stretching the skin as taut as the head of a new-brac’d drum, and she waddled along the rope like a goose over a barn threshold.’

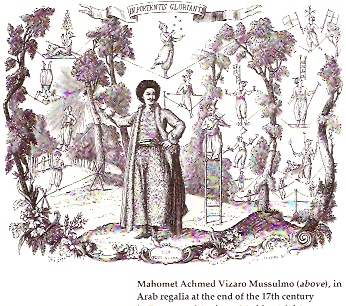

Yet another Turk astounds the French: ‘Near the end of the seventeenth century, there lived a Turk who would walk up a steep rope attached to the top of a mast erected inside the Jeu de Paume at the Saint-Germain fair. He would attach his balance pole to a revolving disc at the top of the mast and spin round upon it like a top whipped by a schoolboy. Then he would dance head down, feet up, in time to a violin. Finally he would walk down the rope backwards, even though it was almost vertical.

Spectators could only tremble for his life, which he was to lose shortly afterwards at the Troyes fair in Champagne. A well-known English rope-dancer from the same company, jealous of the Turk’s fame, was suspected of having greased the lower part of the rope under the pretext of chalking it, while the Turk was spinning round up above. Descending the rope backwards, he failed to notice it, and the fact that he was walking barefoot contributed to his fall. Such crimes are not uncommon among those who aspire to excellence in the Arts.’ [Jacques Bonet, “Historie Générale De La Danse Sacrée Et Profane”, 1724]

At the turn of the seventeenth century, while Paris [France] mountebanks were being persecuted by legitimate actors for trying to establish their theatres in the Boulevard du Temple, their London counterparts found freedom for their art in the pleasure gardens of Islington. The discovery of a chalibeate spring in the vicinity and the nearby excavation of Sir Hugh Myddelton’s New River, London’s first artificial water supply, encouraged a Mr Sadler to open the area for recreation. People thronged to see the great works of Sir Hugh, to fish in the New River and to take to the waters, ending the day at Mr Sadler’s establishment.

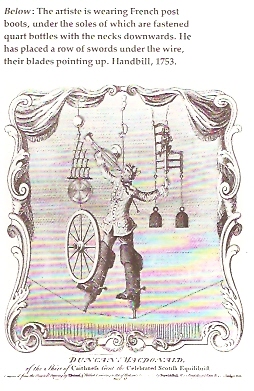

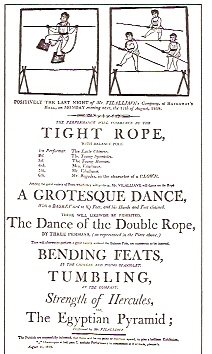

At five p.m. it all started: music, dancing, singing, tumbling, pantomime, and above all rope-dancing. ‘At Sadlers Wells Musick House, set among gardens, there appeared on a wire no thicker than a sewing thread, the figure of the Scottish equilibrist, with a firing of pistols, a blowing of trumpets and a swinging and rolling of wheel-barrows.’

‘The reader will pardon the introduction of the substance of an advertisement inserted in “The Postman”, August 19, 1703, by Barnes and Finley, who, after the usual exordium of their superior excellence, mention that the spectator will “see Lady Mary perform such curious steps on the dancing rope.” Chetwood, in his “History of the Stage”, mentions this Lady Mary who was the daughter of noble parents, inhabitants of Florence, where they shut her up in a nunnery. Despite this loving care, their beautiful offspring caught sight of a Merry Andrew, who unfortunately saw her. In consequence, a clandestine intercourse took place; an elopement followed and finally this villain taught her his infamous tricks, which she exhibited for his profit till vice had made her his own.

Lady Mary is subsequently noticed in “Heraclitus Ridens No 7”, by Earnest, who says: “Look upon the old gentleman; his eyes are fixed upon my Lady Mary: Cupid has shot him as dead as a Robin… Poor Heraclitus! He has cryed away all his moisture, and is such a dotard to entertain himself with a prospect of what is meat for his betters!”

The catastrophe of the Lady Mary was dreadful: her husband, impatient of delays or impediment to profit, either permitted or commanded her to exhibit on the rope when eight months had elapsed in her pregnancy: encumbered by her weight, she fell, never more to rise; her infant was born on the stage, and died a victim with its mother.’ [James Peller Malcolm, “Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London During the Eighteenth Century, Including the Charities, Depravities, Dresses and Amusements of the Citizens of London During the Period”, 1808.]

At the turn of the eighteenth century, in France the mountebanks leave the fairs, their traditional setting, and start building theatres where they can perform all year round.

The actors of the Comédie Française in Paris have every reason to fear the newcomers: they could lose their audience. (Ita populus studio stupidus, in funambulo animum occuparat… ’ Our spectators were distracted by rope-walkers, said Terence, writing about what happened at the first performance of his play “Hecyria”, in AD 333, when a troupe of funambules was rumoured to have arrived in town.)

They might also, by association with low types, lose the favour of the King: a favour painfully acquired over a century. Old mountebanks themselves, they are anxious to preserve their recently acquired status. Which is why they use their favour in court to protect themselves by a series of decrees.

On 17 April 1709, at the direction of the Comédie Française and the Opéra, the police forbid the newcomers to perform musical scenes. Farce and comedy are likewise suppressed, even in the fairs. In February 1710, they are forbidden to speak, sing or dance except on the rope. Finally in 1719 the shows of the Boulevard de Temple are suppressed altogether, owing to the building of the nearby Académie Royale de Musique.

The Revolution will temporarily lift these prohibitions.

‘No more are found the famous rope-dancers and flyers watched with awe and trepidation by their audience, who never knew that they chewed a root called ‘dormit’ to prevent vertigo like the goats and chamois who eats its leaves before climbing the mountain heights of the Pyrénées.’ [Jacques Bonnet, “Histoire Générale De La Danse Sacrée Et Profane”, 1723]

In England, even if they do get a licence the rope-walkers have to stay within the confines of the fair. At Stourbridge, the mountebanks are only granted space when the trading is over and the local gentry drops by to be amused.

‘In a word,’ writes Daniel Defoe in 1723, ‘the fair is like a well-fortified city, and there is the least Disorder and Confusion (I believe) that can be seen anywhere, with so great a concourse of people.

Towards the latter End of the Fair, and when the great Hurry of Wholesale Business begins to be over, the Gentry comes in from all parts of the County round; and tho’ they come for their diversion, yet ‘tis not a little Money they lay out; which generally falls to the shares of the retailers, such as Toy-shops, Goldsmiths, Braziers, Ironmongers, Turners, Milleners, Mercers, etc. and some loose coins they reserve for the Puppet shows, Drolls, Rope-dancers and such like, of which there is no want… ’

‘Let this small monument record the name

Of Cadman, and to future times proclaim

Here, by an attempt to fly from this high spire

Across the Sabrine stream, he did acquire

His fatal end. ‘Twas not for want of skill,

Or courage to perform the task, he fell:

No, no - a faulty cord, being drawn too tight,

Hurried his soul on high to take her flight,

Which bid the body here beneath good night.’

In seventeenth century England feather beds were provided as a precaution: ‘A rope stretched from the top of the tower of All Saints Church (Hertford), and brought obliquely to the ground, about four score yards from the bottom of the tower, where, being drawn over two strong pieces of wood nailed across each other, it was made fast to a stake driven into the earth; two or three feather beds were then placed upon the cross timbers to receive a performer when he descended and to break his fall. He was also provided with a flat board, having a groove in the midst of it, which he attached to his breast; and when he intended to exhibit, he laid himself upon the top of the rope, with his head downwards, and adjusted the groove to the rope, his legs being held by a person appointed for that purpose, till he had properly balanced himself. He was then liberated, and descended with incredible swiftness from the top of the tower to the feather beds, which prevented him from reaching the ground. This man had lost one of his legs, and its place was supplied by a wooden one, which on this occasion was furnished with a quantity of lead sufficient to counterpoise the weight of the other. He performed the feat three times the same day: the first time he descended with his hands empty, the second time he held a trumpet, which he sounded as he passed down, and the third time he had a pistol in each hand, which he discharged in the course of his passage.’ [Jehosaphat Aspin, “A Picture of the Manners and Pastimes of the Inhabitants of England from the Arrival of the Saxons Down to the Eighteenth Century, Selected from the Ancient Chronicles and Rendered in Modern Phraseology”, 1825]

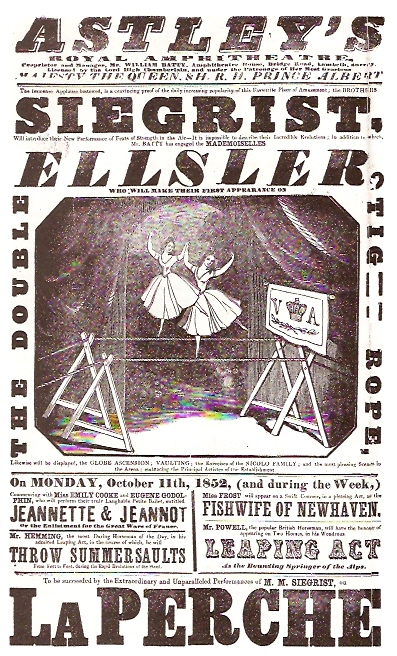

In the late eighteenth century, Philip Astley of the Kings Royal Regiment of Light Dragoons, an outsider to show business, created the circus as we know it today.

He was the author of the best-selling riding manual “The Modern Riding Master” (1775). His revolutionary idea was to turn the practising routine at his riding stables at Royal Grove under Westminster Bridge into a public spectacle, to which he added pantomime, songs and acrobatics: hence the familiar circus ring of today. His second stroke of genius was to turn his eyes to Paris and, in 1782, join forces with Franconi, the descendant of a family of mountebanks from Venice, Together, Astley and Franconi worked out the modern-day system of quick-fire turns and installed their own amphitheatre, the Cirque Olympique, in the Boulevard du Temple to test the formula. It was a success. In the same year, Astley was received at Versailles and dubbed “The English Rose” by Marie-Antoinette. He skidded through the Revolution, putting on Bastille Day Celebrations, but he had to flee France when the Convention declared war on England in February 1793.

Astley’s name survives on this Poster from 1852

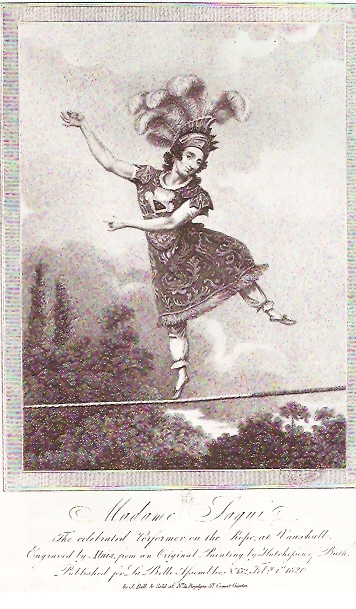

On 26 February 1786, Hélène Masgomieri, the ‘Black Virgin’, gives birth to Marguerite Lalanne at Agde, in the Hérault. The child becomes Madame Saqui and lives for eighty years.

When he has a chance to run across tightrope walkers, the young artist should never fail to observe them closely. [Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749-1832) Writer of Poetry, drama, literature, theology, science]

The modern circus’ habit of ‘foreignising’ artistes’ names already exited in medieval times, when merchants sponsored tight-rope acts high above the fairs as advance publicity. Rope-walkers had to be at least as exotic as the foreign goods they advertised. But the public liked them to be foreign for another reason.

French, Chinese and Turks were the most reputable rope-walkers, but they were also, at one time or another, embodiments of traditional enemies, either straight-forwardly aggressive like the Turk, or darkly threatening like the Chinese. The Pope anathemized the Turks and preached Holy War. But a few rope-walkers managed just the same to make their Turkish names famous in Christian countries. Perhaps this is because the excitement of watching such acts is enhanced for the native onlooker by a pleasurable sense of guilt - his secret sin of hoping the hated foreigner will fall.

As the Chevalier de Jaucourt notes under ‘Funambule’ in “La Grande Encyclopédie”, ‘The pleasure we get from watching a tight-rope walker is the same emotional attraction which makes us run after those objects capable of arousing our passions, even though those objects might do us harm.’

‘A wight there is, come out of the East,

A mortal of great fame;

He looks like a man, for he is no beast,

Yet he has never a Christian name.

Some say he’s a Turk, some call him a Jew,

For ten that bely him, scarce one tells true,

Let him be what he will, ‘tis all one to you;

But yet he shall be a Turk.’

[James Caulfield, “Portraits, Memoirs and Characters of Remarkable Persons, From the Reign of Edward the Third To The Revolution, Collected From the Most Authentic Accounts Extant”, 1794.]

‘Such was the effect of the rope-flyers who visited New England, and after whose feats children of seven were sliding down fences and wounding themselves in every quarter.’ [“Dr Bentley’s Diary”, Boston, USA, 31 July 1792]

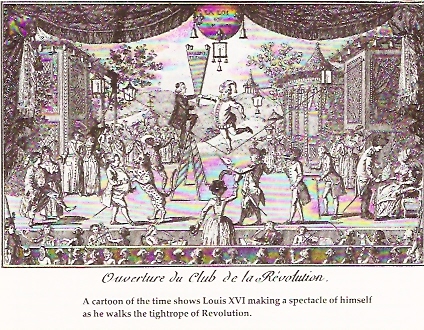

Louis XVI’s (1754-1793) brother, the Comte d’Artois, takes tightrope-walking lessons from Madame Saqui’s father, Navarin le Fameux, who comes to the Palace especially. In her memoirs, Madame Saqui remembers her father wishing her ‘une jambe aussi brillante’ as the future King’s.

The Court follows the royal fashion. The Comte de Cheverny writes in his memoirs: ‘The Baron de Vioménil, the Comte d’Ourches, the Marquis du Hautoy kept me company, as well as the Chevalier d’Aspremont, and we all took rope-walking lessons. We were coached by a rope-dancer from Restier. The best among us was the Comte d’Ourches, who was strong and agile.’

The happy few at Court tried to keep abreast of the Enlightenment, but they only aped l’Esprit des Lumieres, taking up a shepherdess’s lifestyle like Marie-Antoinette at Trianon for just one season, or playing at being a locksmith like the King, or taking rope-walking lessons like his brother. These experiments were short-lived and superficial. Instead of pointing to a change of outlook, they turned out to be harmless hobbies. Tradition prevailed.

The Revolution was to sweep away these velléités.

After the French Revolution (1788-1799), Sadlers Wells Theatre put on a play called “Gallic Freedom: Or Vive la liberté!” which staged the assault on the Bastille and ended with Liberty rising from its ruins on a tightrope.

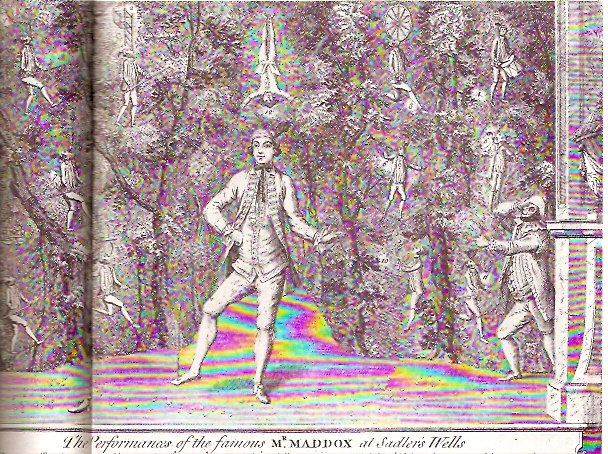

Anthony Maddox at Sadlers Wells Theatre, London 1752

The good people of Boston, USA were slow to allow playhouses and entertainers among them, but on August 10, 1792, the “New Exhibition Room, Board Alley,” for so they styled their first theatre, was opened. Plays as such were still under a cloud, so the clever manager of the “Exhibition Room” announced them as “Moral Lectures”, thereby fooling nobody but the pious who did not attend.

On the 12th, was presented a moral lecture, “Venice Preserved”, with “Dancing on the tightrope by Monsieurs Placide and Martine” and “Various feats on the slack rope by Mr Robert” between the acts. Four days later we find Shakespear’s “Taming of the Shrew” masquerading as “A favourite moral lecture called… Catharine and Petruchio” and again Monsieurs Placid and Martine held forth while the company changed their meagre scenery and costumes.

January 25th found the company still as popular as ever with new features to attract the populace, including a song: “Whether My Love,” by Madame Placide, this being her second attempt to sing in English.’ [R.W. Vail, “Random Notes”, 1933]

When he’s above us, we are below him,

Yet with not ourselves together:

We dare not hazard a leg or a limb,

For cracking a parcel of either:

But he the predominant lord of the cord,

Domineers o’er the peasant, the knight and the lord,

And honestly shews fair play above board,

But yet, he shall be a Turk.

[James Caulfield, “Portraits, Memoirs and Characters of Remarkable Persons”, 1794]

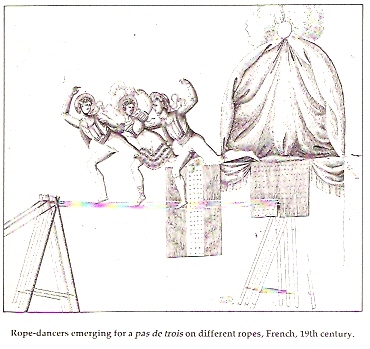

Sir Placide and Petit Diable, back from London, have just appeared again on the horizon. Nicolet has lost no time announcing in his ridiculous posters that they will perform a “pas de deux” on the same rope. (Theophrastus tells us that the Greeks called this type of dance a “cordax”. It was done in theatres similar to those in our fairs. Those who attended these places took pleasure in the variety of obscene and indecent poses the dance would present.)

Everyone is hurrying there to see the two men walking uneasily on a rope, falling off one after the other, and laughing at their own clumsiness, and the audience who have been stupid enough to come and see them. They are now to be seen on the boulevards and in town dressed as only the English can, and riding horses of that country, as ridiculously as they walked the wire. As for their behaviour, it is still the same. [“Le Chroniqueur Désoeuvré Ou L’Espion Du Boulevard Du Temple”, by an Anonymous Author, 18th Century]

‘The lowest step of equilibrist art is the globe performance. Walking upon the rolling-ball, forward and backward, vaulting and dancing upon it, are the A B C of the profession.’ [Hugues Le Roux and Jules Garnier, “Acrobats and Mountebanks”, 1890]

‘A proverb is current behind the scenes of the circus, to the effect that love destroys the centre of gravity in tightrope dancers, and as a rule equilibrists - that is to say the true artists, not the pretty girls who use the cord as a springing board - might rank with the Roman vestals. Their reputation is their fortune, and they are carefully guarded by their parents. It is not only a question of averting the danger of maternity, which ends the artistic career of an equilibrist. No risk must be encountered of anything that could damage the artist’s health; and, therefore, those who are particular on these points can enjoy the performance of an equilibrist without any uneasiness about her private life’ [Hugues Le Roux and Jules Garnier, “Acrobats and Mountebanks”, 1890]

‘The beauty of the performance lies in the delicacy, variety, facility and grace of the artist’s movements, and on this account women excel as equilibrists, for men cannot reconcile themselves to the suppression of their strength.’ [Hugues Le Roux and Jules Garnier, “Acrobats and Mountebanks”, 1890]

The famed mime Deburau (1794-1846) started life as a top of the so-called Egyptian Pyramid, which rested on the shoulders of a certain Monsieur and Madame Godot.

‘One day M. and Mme Godot, “First Funambules of Europe”, and already somewhat past their prime, happened - by some trick of fate - to be drunk… It is Deburau’s turn to go up and he goes up bravely, this tall man, blissfully unaware of what kind of wine is supporting him. Suddenly, M. Godot trembles, Madame trembles, Monsieur leans on Madame, Madame leans on Monsieur: the Egyptian Pyramid shivers, the Egyptian Pyramid shudders, the Egyptian Pyramid crumbles slowly to the ground, with Deburau the first to fall.

Deburau is injured, but the audience just laughs. Yes, the audience bursts out laughing, fit to bring the roof down. Our poor artiste, battered and bruised, regards the pit with tears in his eyes. The pit only redoubles its hilarity. Ungrateful public! as the actor Baron would so rightly say.’ [Henry Thétard, “Coulisses et Secrets”, 1934]

A USA Handbill of 1812

Marguerite Lalanne’s stage name as a young girl was ‘Mademoiselle Forioso’, after a famous rope-dancer of the time. She married Jean-Julien Saqui, with whom she is buried at the Père Lachaise cemetery under a column surmounted by an urn, in the 40th division, near the pathway. But Madame Saqui (1786-1866) had better ideas than touring with her husband’s family troupe.

She set out alone for Paris, where she was to make her name famous.

She arrived at the Tivoli, the Luna-Park of Paris, just in time to see Forioso fall from his rope. It was her moment: she instantly replaced the fallen star. Her fame grew from one day to the next. Paris thronged to see her and adopted her. She became a trend-setter: everyone wore ostrich-feathered hats ‘a la Saqui’, or bought boxes of sweets with her portrait on.’

Madame Saqui

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) had Madame Saqui walk up a rope to light the famous Ruggieri fireworks displaying his new Empress’s initials as a welcome in the Paris sky.

John Harvey Darrel, Chief Justice of Bermuda, described a similar feat when he saw her perform at Vauxhall Gardens in 1816:

‘Suddenly a bell rings, the music ceases, away runs the whole party, you follow, unknowing why or whither. But in spite of the tumult and chattering you shortly arrive at the end of one of walks and perceive that fireworks are about to be let off. In a moment the whole air is ablaze, crowns, hearts, initials and various figures show themselves in meteoric flashes and disappear, attended by sudden flashes which gleam on all sides through the wreathing smoke and culminate in a terrifically grand spectacle: the heroine of the piece [Saqui] appears as a rope-dancer, ascends the cord which at a considerable angle is rigged to a height of seventy or eighty feet. Through the smoke and flames she rapidly climbs the blazing pinnacle to the top where rockets seem to graze her in her course, exploding above, beneath, around her and spangling her flimsy dress with their scintillations. Every moment you expect to see the rope severed, to see her precipitated from the dizzy height. But still she supports herself like those fabled Elves which ride upon the storm.’ [Bermuda Historical Quarterly, 1949].

‘A human figure moving in a burning atmosphere and at so great a height from “solid earth“ presents a most imposing spectacle. For ourselves we can only say that it rivals what our imagination has conjured up from the enchantments of the Arabian nights. This surprising female, sparkling with spangles and tinsel and her head canopied with plumes of ostrich feathers, ascends the rope to a man seated at the top in the midst of blue lights and a hundred wheels and stars and rockets; thence she again descends with a rapid step, stopping only for a few moments near the centre of the long and dazzling line.’ [The Literary Gazette, 1817]

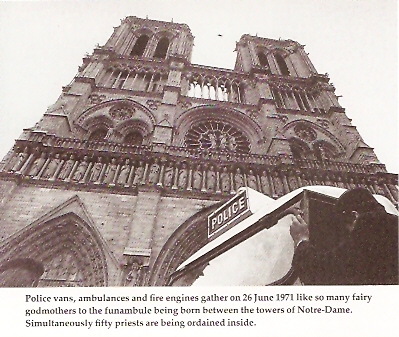

Madame Saqui saluted the birth of Napoleon’s long awaited heir, the King of Rome, by walking between the towers of the cathedral [Notre-Dame, Paris]. Since the Emperor had divorced Josephine for Marie-Louise, the fruit of such a union was considered a crime by the Church and therefore Saqui’s Notre-Dame walk sacrilegious.

An old lady who lived to be a hundred had a mass said once a year for the soul of Saqui, which she said had been condemned to dance between heaven and earth for two hundred years, taking a rest only when there was a rainbow to lean on.

Madame Saqui gets invited to the famous ‘Dîner des Bêtes’, at which each guest personifies an animal. Is it mere coincidence that she is given the role of an eagle? Or is it a portent of her relationship with the Emperor, now at the height of his glory? For a while now she has been dedicating her performances to ‘the hero’ of Eylau, Friedland, Wagram… which makes her an obvious choice to perform at a party given by the Emperor for his Guards. That night a firework grazes her arm and she nearly falls from the rope. She manages to lie down, then slides towards the pole. It seems her act is over. Napoleon goes to see her and out of compassion touches the wounded arm. She screams with pain, then defying his orders to keep still, gets up and announces: ‘Just as you are the Master of your Guard, so am I master on the rope.’ Napoleon is captivated. He calls her ‘L’Enragee’. From now on she is to follow his bivouac, entertaining the soldiers between assaults.

Returning from the battlefields, she mimes on the rope some of the action she has seen. With a sword in her hand and wearing a golden cuirass, she illustrates her stories by imitating some general or other, all to the glory of the Emperor. It seems that the two eagles understand one another.

By 1812 Madame Saqui is back touring Europe, this time in great pomp, her dozen faithful Turks escorting her carriage stamped with the eagle of the Emperor. For a while she is ‘The first Funambule of his Majesty the Emperor’, until one day in Agen some official notices the eagle and complains. Orders come from Paris to have it removed. Saqui is humiliated and returns to more pastoral scenes. But she won’t give up fireworks of her mock battles. Soon she will have to change her act anyway, for the Eagle has fallen with the retreat from Russia. And now comes Waterloo.

For the entrance into Paris of the Duchess of Berry on 17 June 1816, Madame Saqui decides to revive the 500-year-old ceremony. As the Duchess passes through a vault of white flags, Saqui appears out of nowhere, as if by enchantment. Then she enters the vault and throws a crown of golden laurels over the Duchess’s head.

‘20 April - 6 May 1823, Madamoiselle Romanini the eldest, artiste orichalcienne, together with her two sisters, arrives from the Cirque Olympique in Paris. An artiste orichalcienne dances on the fil d’archal [wire]. Mlle Romanini did more than dance. She would mount the wire while it was moving and stand upon it, following its movement.’ [J.E.B. (De Rouen), “Histoire Complète Méthodique des Théâtres de Rouen”, 1880]

Admiration is a sign of weakness if too easily given - one should not reward equally a rope-dancer and a poet.’ [Honoré De Balzac, “Illusions Purdues”, 1843]

Napoleon [Boneparte] defeated, Madame Saqui goes to London where she performs at Vauxhall Gardens. It is a visit she hasn’t been able to make while France and England were at war. The ‘First Acrobat of His Majesty Lois XVIII’ makes her first public appearance dressed in flesh-coloured tights. Victorian London murmurs its disapproval. As soon as Saqui realizes what is wrong, she takes one of her Turks backstage and reappears almost immediately wearing his trousers. In this outsized bouffant costume she carries on as if she had always intended to appear so dressed.

‘In the midst of a great burst of fireworks, Bengal lights glimmering faintly in the clouds of smoke, she (Saqui) stands on a rope, sixty feet up, and follows a narrow and difficult path to the end of her journey. Sometimes she is completely hidden from our eyes by the billowing waves, but from the way she walks, so self-assured, one would think an Immortal was walking peacefully towards her celestial home.’ [Lerouge on Madam Saqui at Vauxhall]

Madame Saqui gives the first of many farewell performances in 1845. The poet Théodore de Banville reports: ‘Not bothering to admire her acrobatics, I looked instead at the face of the dancer and saw the pitiful remnants of a superior beauty. Suddenly, as I watched, she became pale, her lips tightened, her eyes started from her head and a murmur of pity and sympathy arose from the crowd: Madame Saqui had just failed to execute one of her finest passes. I had forgotten its name, but it didn’t matter for I was so absorbed by the pathos of her looks. Three times she tried with terrifying effort to overcome her difficulty, and three times her exhausted body betrayed her courage. Nothing could express the anger, despair, and the vast remorse she hid under her smile.

Madame Saqui was honoured with flowers and applause, but just as she was about to leave the stage her strength failed her and she broke down in tears. After the show, she was removing her golden helmet for the last time, one of her old friends, a writer now dead, introduced her to me: “You want to be a poet”, she said with a soft sad smile, “but can’t you see what glory is?” [“Souvenirs” 1882]

She was to walk the tightrope for another twenty years.

In 1852 at the age of sixty-six, Madama Saqui undertakes a tour of Spain. On the way back she is robbed of her takings by a highwayman, and the newspapers take up the story. Saqui is in the news again. “L’Illustration” writes: ‘If she goes on dancing, sometimes even hanging by her heels, it is because the most infamous bandit of all Spain robbed her recently in the Sierra-Morena, taking from her everything but her pride.’

Madame Saqui aged 66 in the guise of a pilgrim to Saint-Jacques de Compostelle

At Madame Saqui’s theatre, the whole pantomime changes every other day, the Turks have fabulous new costumes, and the acrobats are famous for their brilliance. Everything goes well until the death of M. Saqui: this self-effacing being has always lived in her shadow, busy with the theatre’s books. His replacement by Saqui’s brother Lalanne proves a disaster. He invests all her money in madcap ventures such as luminous top-hats, patented in vain by the poor man.

One day she steps into the carriage of one Bertrand, a man she vaguely knows from the theatre, who is making a living taking rides and selling butter. She is unhappy about the ride, and complains. The tone rises. She tells him he is nothing but a peddler of lard and before parting with the fare accuses him of being a highwayman. Bertrand remembers the insult and swears to take revenge on the famous acrobat. He goes to visit his friend Fabien, an umbrella salesman, and persuades him to back his plan to build a theatre next to Saqui’s. Adding insult to injury, the new theatre is to be called the Théâtre des Funambules. It is an instant success, with the young comedian Frédérick Lemaître and also the mime Deburau, who cut his teeth at Madame Saqui’s. Both performers will later figure in Marcel Carné’s film “Les Enfants du Paradis”, played by Pierre Brasseur and Jean-Louis Barrault.

Madame Saqui became vain and imperious with age. She performed only when she felt like it and fantisized continually about her past: ‘I have climbed the ladder of a mountebank’s life,’ she boasted to a journalist come to interview her, ‘from the carpet laid on the cobblestones of the street, where alone at the age of five I had to earn my living, to the draperies of gold and silk so often hung for me in palaces of Kings… ’ [Paul Ginisty, “Memoirs D’Une Danseuse De Corde”, 1907]

La Petite danseuse (detail) by Adolphe-François Pannemaker, Brussels, Belgium 1800’s

‘There is evidence that this Mme Austen, the “Ariel of the Tightrope”, was spurred on by rather special competition in the development of her ability to take the spectator’s breath away. From John McCabe’s journal we learn that the lady made her first particularly sensational tightrope ascension and descension across a busy street in the heart of San Francisco, USA - from the lot opposite the International Hotel to the top floor of that building. This feat she accomplished at about eight oclock one morning in August 1855; the aerialist had intended to give her performance on the preceding evening, but had been prevented by too strong a wind. Early in October she did succeed in making a night ascension. But now an obtrusive rival appeared. At the same place, some three weeks later, one Signora Caroni, a member of Professor Risley’s troupe of gymnasts, performed the same act without using a balance pole; and then, on the third night afterwards, with Signor Caroni as her partner, she shared the honours of the first double ascension across the street. But not yet was the Italian upstart satisfied with the proof of her superior skill and daring. A month later, when the Risley troupe and the Stark’s dramatic company were sharing the boards at the Union Theatre, Signora Caroni made an ascension “from stage to dome”, over the heads of the audience! Mme Austen would be obliged to wait a while for the perfect opportunity to meet this challenge; but it came, on a March evening of 1857. At the Metropolitan the original “Ariel of the Tightrope” made an ascension, without the aid of a balance pole, from stage to upper tier - a performance described by a not unduly flattering reporter as “terrific”.’ [G.R. MacMinn, “The Theater of the Golden Era in Califormia”, 1941]

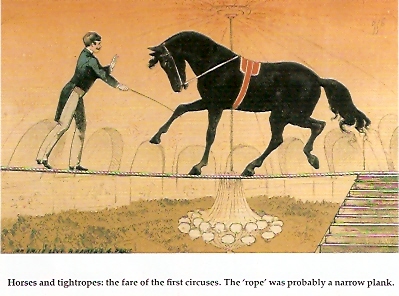

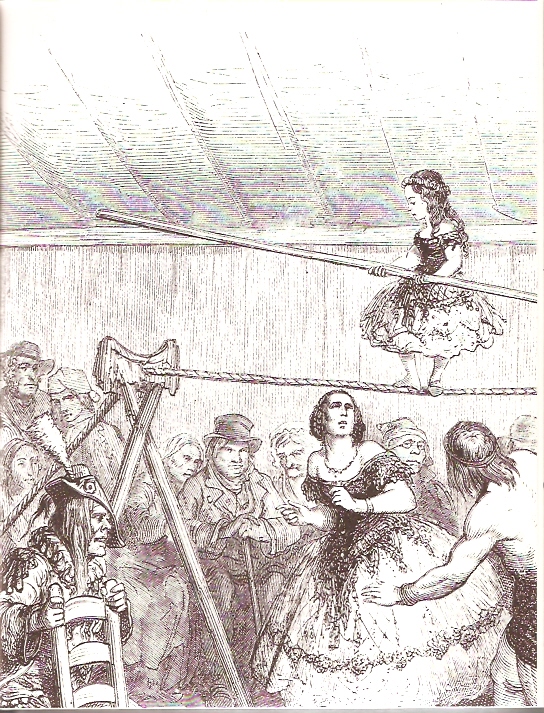

Right from the start, rope-dancers were integrated into the circus. But it was the sight of pretty women and clowns on low wires that was sought after, not the highly individual skill of the lonely high-wirer. From the moment Phillip Astley invented the modern circus in the 1780s the funambules became no more than pretty dancers on a silver wire, filling in between a learned dog and a conjurer.

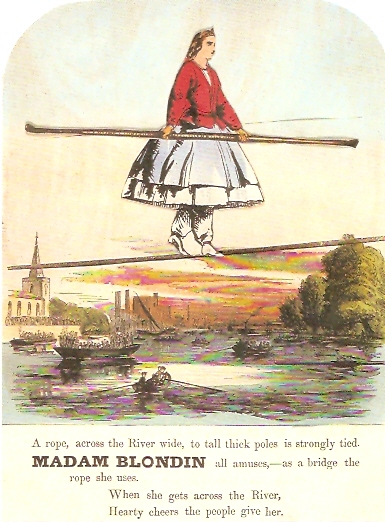

Was it mere coincidence that in the nineteenth century, as the circuses prospered and multiplied, Blondin appeared, who would once more mystify the world with his great walks?

On 28 February 1824, at Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais, is born another tightrope walker of genius, one Jean-François Gravelet, later named Blondin after his first instructor. A Pisces like Madame Saqui, he will live like her for the high wire and die like her in bed after a long and dangerous existence, days before his seventy-third birthday. He rests in Kensal Green Cemetery, London.

‘Gabriel Ravel (1810-1882) takes so many liberties with the rope that one forgets the dangers which surround him. His cool approach disguises from his audience the precipices opening under his feet’ [“Journal Des Theatres”, 1830]

Gabriel Ravel was to notice the young Blondin at Ducrow’s School of Acrobatics in Lyon and take him to tour America with his family of acrobats.

Blondin himself started in the circus. The famous tightrope-walker Gabriel Ravel adopted him as a son, which compensated in part for his raplatie (earth-bound, non-circus) origins. But it didn’t last. Circus routine couldn’t quench his thirst for glory and he longed for freedom. In possession now of an infallible hire-wire technique, he felt lost and underestimated among all the other acts. Without realising it, he was embarking on a lifetime’s search for the heroism of Napoleon’s wars he used to hear about at his Father’s knee. It was a folie de grandeur which his strength of purpose would turn to glory. A hero stands alone. He knew that. And so he left the circus forever.

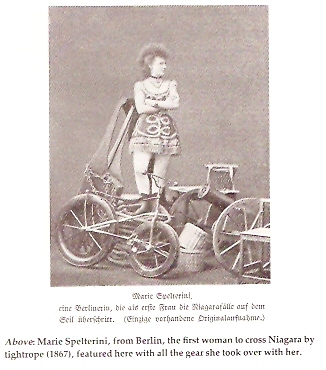

At the age of 35 on 30 June 1859, Blondin first accomplished the feat of crossing the gorge below the Niagara Falls - a distance of around 1100 feet using a tightrope, thus creating his celebrity and fortune. The tightrope was 50 metres (160 feet) above the water, nearly half a kilometre (over quarter of a mile) long and just 7.5cm (three inches) in diameter. Blondin’s obsession with the Niagara Falls continued and he actually made a further 16 crossings, each one more daring than the last:

He crossed it blindfolded, pushing a wheelbarrow; once he carried a stove, stopped half way across and cooked himself an omelette and on another time he crossed on stilts. In August 1859 he crossed the gorge with his manager Harry Colcord on his back.*

*See full reports, witness statements and photo Gallery elsewhere on this Website

Blondin’s 1861 show in the [Crystal Palace, London] building now demolished was a triumph. He hung his rope across the great arch of the building, a hundred and seventy feet from the ground. The rope was rumoured to be the same one he used at the Niagara Falls, so many of the visitors ruthlessly helped themselves to souvenirs from the great coil of surplus rope.

At Crystal Palace, only one shadow passes momentarily across his sun, the day Blondin wheels his five year old daughter onto the rope in a barrow. Like the flesh coloured tights of Madame Saqui, it causes a scandal. The sentimental Victorians protest. The impudent Frenchman! Blondin has to stop and wheel a puppet instead.

‘In 1861 a great attraction offered by Cremorne to the public was the crossing of the River Thames [London] on a tightrope by the female ’Blondin’, Madame Genevieve. Her real name was Selina Young, but it would never have done in those days to use so plebeian a patronymic… The tightrope was raised on trestles from Cremorne to the opposite shore. The female Blondin started from Battersea, but when about only six hundred feet from the end of her journey she stopped, and there was a long pause while attendants tried to tighten the remaining portion of the rope, which was sagging too much to make it possible for Madame Genevieve to continue her journey. The rope was tightened and she began to move forward, but as she moved the rope began to swing to and fro, and it was discovered that some unspeakable rogue had cut the guy ropes in order to steal the lead weights. It was of course impossible to proceed, and with the greatest presence of mind the girl threw away her balancing pole, bent down and caught the rope with both hands, swung herself down onto one of the sway ropes, and slid down into the river, where she was picked up by a boat.’ [Walter Scott, “Bygone Pleasures of London”, 1948]

‘To venture in all sorts of situations in which one may not have any sham virtues and where, as with the tightrope-walker on his rope, one must either stay or fall.’ [Friedrich Nietzsche, “Twilight of the Idols”, 1889]

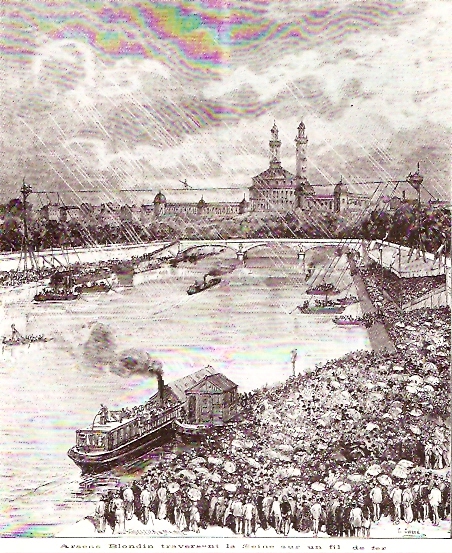

Arsens Blondin, a tightrope walker who named himself after Blondin, crossed the Seine (France) in September 1882 despite the weather conditions

‘She (Oceana) would take up the attitude (on the rope) of reclining in a hammock to exhibit her beauty without too much exertion.’ [Huges Le Roux, “Acrobats and Mountebanks”, 1890]

Oceana Renze

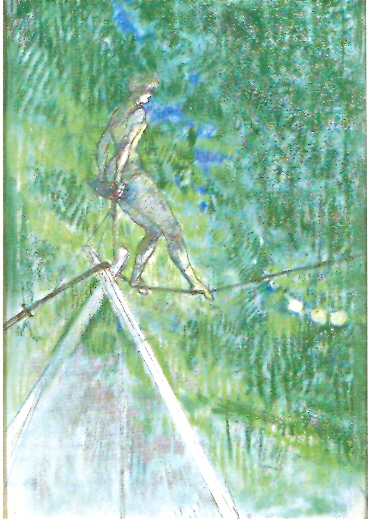

In 1893 Toulouse-Lautrec was committed to a lunatic asylum by his family. According to his doctors, the main symptom of his illness was loss of memory. His friend Joyant, eager to get him released, conceived the following stratagem. To prove the doctors wrong, Toulouse-Lautric was to draw from memory scenes from the popular entertainments of the day. It was in this way that he came to draw with pastel and pencils “La danseuse de corde”.

“La danseuse de corde” by Toulouse-Lautrec

‘Start on a ball, not on a rope or wire,’ says William Sansom in “Pleasures Strange and Simple” (1953). ‘Practice until you can stand on a large globe as it revolves at speed.’

‘The ease with which these feats are performed by practised equilibrists is only apparent. It is not un-exhausting. It costs much mental and physical strain, many performers descend streaming with sweat and remain dangerously unapproachable afterwards. There are several theories as to how tightrope-walking is possible at all. Hypnotic theories, for instance, hold that the point of sight acts in some way as a mesmeric focus. Equilibrists and ascenionists on the rope have admitted to a feeling, after some seconds of concentrated gaze, of peculiar isolation and of a physical attraction towards the guidon; and this, they say, is accompanied by an involuntary stiffening of the muscles that in effect assists the rope-walk. Others say that a concentration of the eyes allows one to listen inwardly with the ears, the sense of hearing being held indivisible from the sense of poise. M. Blondin used to walk blind-folded… lsquo; [William Sansom, “Pleasures Strange and Simple”, 1953]

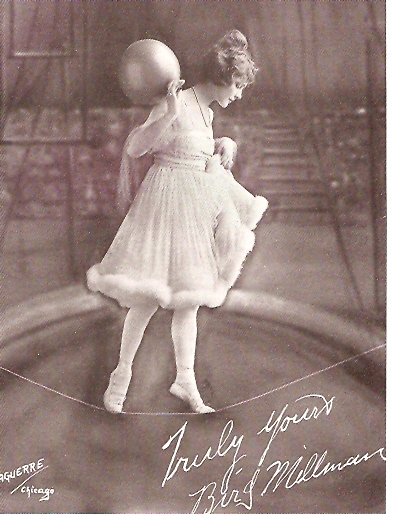

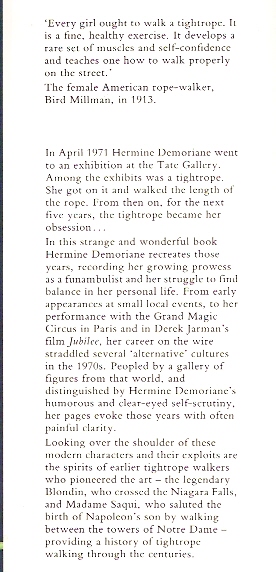

The American rope-walker Bird Millman (1890 - 1940) gave great interviews:

‘To some folks a slack wire is their idea of nothing to walk on. To me, it’s a whole street, with curbing and pavements thrown in.’ “Pittsburgh Post”, USA, May 1913

‘Every girl aught to walk a tightrope. It is a fine, healthy exercise. It develops a rare set of muscles and self-confidence and teaches one how to walk properly on the street.’ “Milwaukee News”, USA, 1913

Bird Millman (USA)

‘The spellbound audience stares amazed at the fairy-fantastic ethereal aspect of the graceful white figure far above them, but I know that I am in the presence of the veritable Queen of the air, for I have seen the little diamond cross quivering at her breast. Frieda Birkeneder always wore that little cross; I noted its gleam when she first glided along the starry dome of the Berlin Winter Garden, and I saw it shimmer through the red blood that drenched her white tights when they carried her unconscious body from the ring of Lisbon’s ’Coliseo’. The accident took place at their third night’s performance in Lisbon; on the opening night her brother Karl fell, but that night Frieda had the worst mishap that can befall a cyclist on the highwire; she lost a pedal, and in her fall she struck one of the wire cables that connected her rope with the ground. She was carried out of the ring, but quickly recovered consciousness and insisted on being led back, battered and bruised and bloodstained, to take the call. She sustained some deep, painful cuts, but she won Lisbon. The Birkeneders were petted like spoilt children; every night the vast auditorium was filled to the last seat with enthusiasts. Bets were freely offered and taken on various issues - whether one of the artistes would fall that night, how old the various members of the troupe were, how long they rehearsed and whether they should accept the invitations given to them; in short, the Birkeneders were the central focus of the town’s interest.’ [August Köber, “Circus Nights and Circus Days”, 1931]

‘To think of you dancing on the tightrope! You who aught to live in luxury!…’ [Maurice Leblance, “Dorothy, Danseuse De Corde”, 1923]

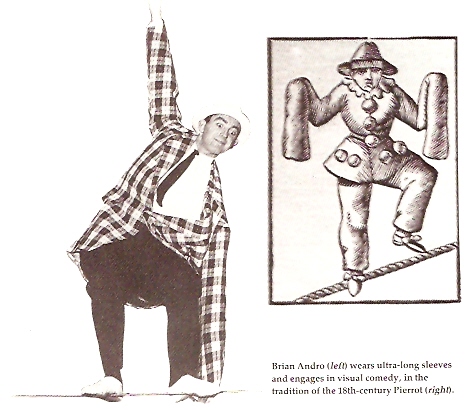

August Köber, in “Circus Nights and Circus Days” (1931), describes ‘a young man, clad in white flannels and carrying a Japanese parasol, who proceeded to dance an extravagant cakewalk, in the course of which he tripped, stumbled, twisted and wobbled, balancing himself in precarious but comic attitudes on alternate feet, kicking out wildly and making frantic clutches at the empty air. But when his performance was finished he put his hands in his pockets and walked erect with light steps and easy bearing to the platform at the further end of the wire.’

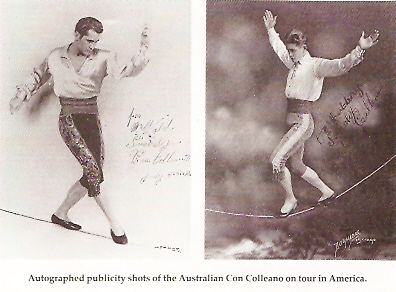

In the twenties and thirties, Con Colleano (1899-1973) would dance tangos and fandangos on the wire, and take his trousers off during a backward somersault to appear in tight-fitting matador’s breeches. He would then fight an imaginary bull with his cape.

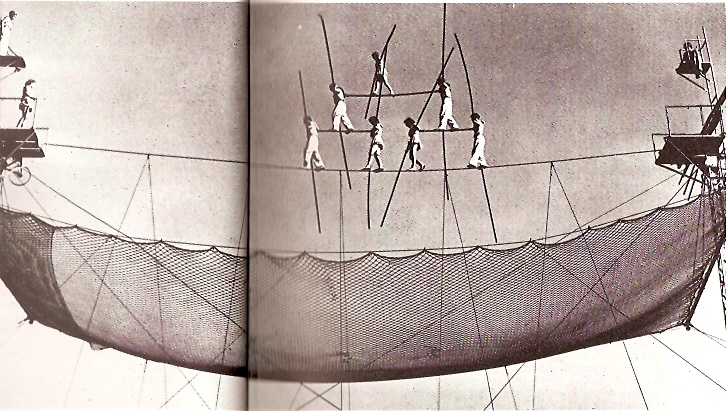

In 1946, at the Ringling Circus, Karl Wallenda realised his lifelong ambition of a seven-man pyramid, in three tiers of four, two and one. Two pairs of men carried bars on which stood two further men bearing a third bar for the top-most, a woman balancing on a chair. The pyramid ran for fifteen years without any trouble.

In 1962 it crumbled, causing two to die.

Wallenda’s 7-man Pyramid

Karl Wallenda carried on alone, practising skywalks. On 22 March 1978 in San Juan, Puerto Rico, a gust of wind blew him off his rope. He was seventy-three.

The gestures of the tightrope walker would look absurd to anyone unaware that he was walking over the void and over death. [Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), French Poet, Novelist, Dramatist, Playwright, Filmmaker]

1962 TIGHTROPE OF LOVE

‘I walk that tightrope of love for you

The rope is narrow in size

But loving you makes it seem so wide

I’m gonna walk that tightrope baby

Am I pleasing you?

Yes I can do it for you’

Charlie Foxx

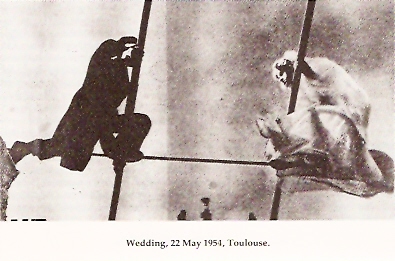

A Wedding Party on the rope, Toulouse, France 1966

ACROBATS

Poised impossibly on the high tightrope of love in spite of all,

They still preserve their dizzying balance

And smile this way or that,

As though uncertain on which side to fall.

Robert Graves [1895-1985]

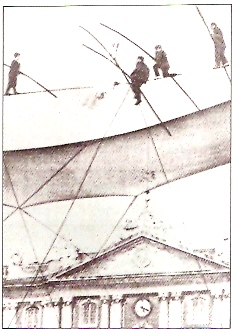

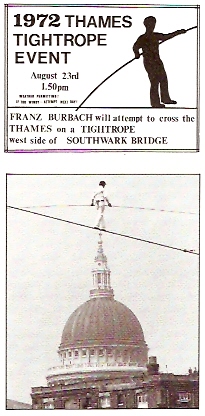

Franz Burbach crosses The Thames, London 1972

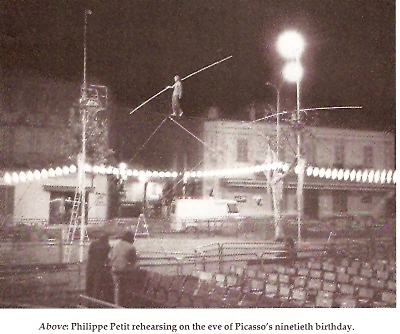

Philippe Petit performing a back roll, 1974

See the 'videos' section to see excerpts of ‘Man on a Wire’ featuring Philippe Petit.

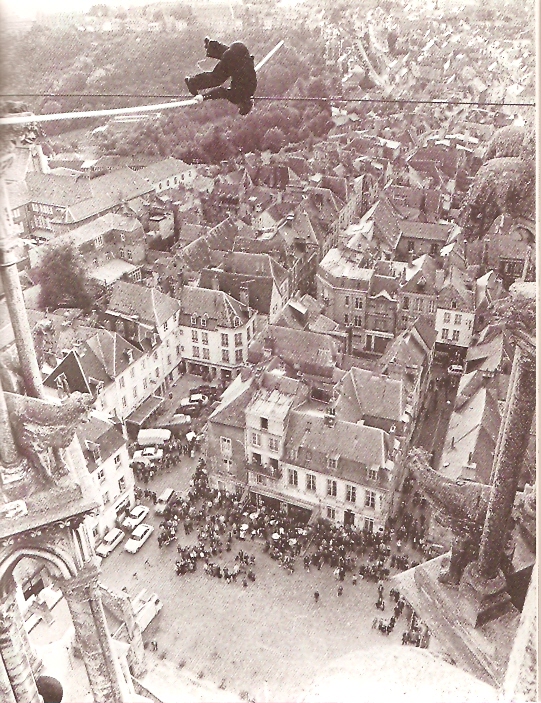

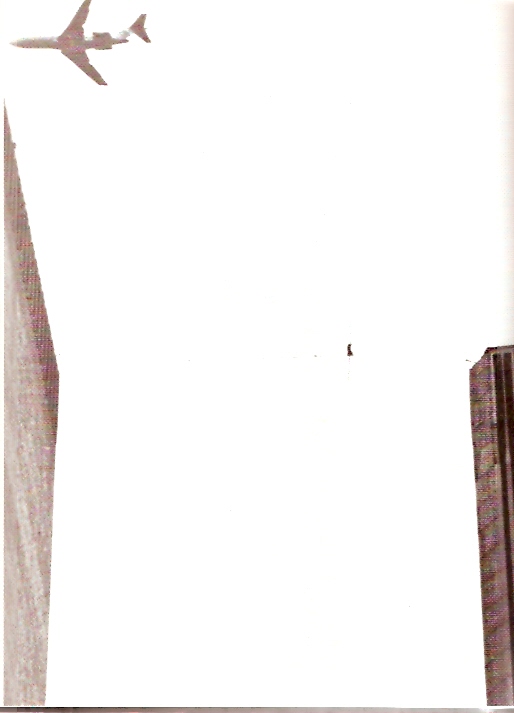

On August 7th 1974, a young Frenchman named Philippe Petit stepped out on a wire illegally rigged between New York’s twin towers, then the world’s tallest buildings.

The astonishing high wire performance by Philippe Petit between the towers of the World Trade Center in 1974 - The Twin Towers High Wire Walk. It is quite ironic that the photograph also captures a plane high overhead, similar to those planes that were crashed into the Twin Towers by terrorists some 27 years later . . . .

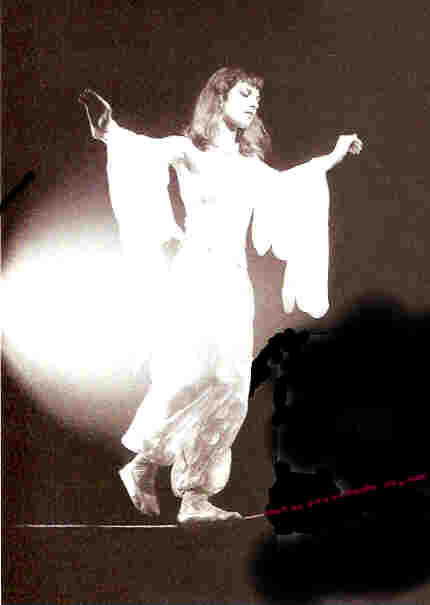

Hermine Demoriane - Funambule & Author, (1970’s)

EARTH

Some people say that my mother is like the earth

earthy, feet on the ground,

but I say feet on the tightrope.

Murphy Demoriane, Aged 6 (1970’s)

ooOoo

Chico at Zippo’s Circus recreates Blondin’s daring feat on the tightrope.

Chico Marinhos celebrated the anniversary of Blondin’s heroic crossing of the Niagara Falls on 30th June 1859 by cooking an egg on a small gas stove 80’ above the ground on a wire above Zippo’s Circus Big Top.

Chico, carrying a small gas stove, crosses to the centre of the wire high above Zippo’s Big Top

He cooks his meal

Enjoying his meal

All the above quotes and anecdotes taken with kind permission from Hermine Demoriane’s book:

“The Tightrope Walker” by Hermine Demoriane - Secker & Warburg, London, 1989.

Signed copies are available, from The Blondin Memorial Trust, 3 Raleigh Street, London Nl 8NW

Please make cheques for £20.00 payable to the Blondin Memorial Trust.

“The Tightrope Walker” by Hermine Demoriane

Prologue:

- Didier Pasquette and Jade Kindar-Martin, two professional funambulists of the Company Altitude, cross the place of the Jacobins - 30m high and 180m length.

- Another excellent low wire performer

- Excellent lady funambulist

- Brazilian Circus from 1932

- Seiltänzerin

- Schlappseil Alexandra

- Slack wire-Dimitar Petrov

- Asian slack wire act

- Ramon Kelvink walks highwire and swaypole at Belfast City Hall.

- This was Alan Martinez of Colombia crossing the Han River, Seoul, South Korea, at the 1st world High Wire championship. His time was 11mins 30.54 seconds to cross 1 kilometer long rope across the river

- First high wire world champioships in Seoul 2007

- Twin Towers Tightrope Walk - Phillipe Petit

- Trailer for “Man on Wire” about Philippe Petit

- Falko Traber the world champion on the high wire

- Camera fastened on funambule David Dimitri’s balancing pole as he balances over a high wire 55 meters above the ground in St. Gallen, Switzerland

Dennis Arundel, “The Story of Sadlers Wells” - Hamish Hamilton, London, 1965

Jehosaphat Aspin, “A Picture of the Manners and Pastimes of the Inhabitants of England” - J. Harris, London, 1825

G. Linnaeus Banks, “Blondin: His Life and Performances” - Routledge, London, 1862

Jacques Bonnet, “Historie génèèle de la danse sacrée et profane” - Paris, 1723

Betty Boyd Bell, “Circus, A Girl’s Own Story” - Warren & Putnam, New York, 1931

Emile Campardon, “Les Spectacles de la foire” - Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1877

Hieronymous Cardanus, “De Subtilitate” - Nuremberg, 1556

James Caulfield, “Portraits, Memoirs and Characters of Remarkable Persons” - London, 1794

Edwin B. Chancellor, “The Pleasure Haunts of London During Four Centuries” - Constable, London, 1925

Jean Cocteau & Man Ray, “Le Numéro Barbette” - Jacques Damase, Paris, 1980

Mathieu de Coucy, “Histoire de Charles VII de 1444 à 1461” - France, 1661

George Chindahl, “A History of the Circus in America” - Caxton, Caldwell, Idaho, USA 1959

William Coup, “Sawdust and Spangles” - Herbert Stone, Chicago, USA 1901

Dean’s Moveable Book, “Blondin’s Astounding Expoits” - London, 1862

William Depping, “Merveilles de la force et de l’adresse” - Hachette, Paris, 1869

M. Willson Disher, “Pleasures of London” - Robert Hale, London, 1951

Witold Filler, “Cyrk” - Warsaw, 1963

Victor Fournel, “Le vieux Paris. Fetes, jeux et spectacles” - Mame, Tours, 1858

Victor Fournel, “Les spectacles populaires et les artistes des rues” - E. Dentu, Paris, 1863

Jean Froissard, “Chroniques” - Michel Le Noir, Paris, 1498

Thomas Frost, “Circus Life and Circus Celebrities” - Tinsley Bros, London, 1876

Paul Ginisty, “Mémoires d’une danseuse de cord” - Paris, 1907

Raphael Holinshed, “Chronicles” - 1577

Hugues Le Roux & Charles Garnier, “Acrobats and Mountebanks” - Chapman & Hall, London, 1890

Isaac Greenwood, “The Circus; its origins and growth prior to 1835” - The Dunlap Society, New York, 1898

August Köber, “Circus Nights and Circus Days” - Sampson Low, Marston, 1931

Maurice Leblanc, “Idorothée, danseuse de corde” - Paris, 1931

Alfred Lehmann, “Unsterblicher Zirkus” - Leipzig, 1939

Henry Morley, “Memoirs of Bartholomew’s Fair” - Chapman & Hall, London, 1859

G.R. MacMinn, “The Theater of the Golden Era in California” - Caxton, Caldwell, Idaho, USA 1941

James Peller Malcolm, “Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London” - 1808

James Peller Malcolm, “Miscellaneous Anecdotes Illustrative of the Manners and History of Europe” - 1811

Louis Péricaud, “Le Théâtre des Funambules” - Leon Sapin, Paris, 1877

Philippe Petit, “Trois Coups” - Hersher, Paris, 1983

Philippe Petit, “On the Hire Wire” - Random House, New York, 1985

Christine de Pisan, “Faits et bonnes moeurs du roi Charles” - 1405

Lord George Sanger, “Seventy Years as a Showman” - Dent, London & Toronto, 1926

William Sansom, “Pleasures Strange and Simple” - Hogarth Press, London, 1953

Walter Scott, “Bygone Pleasures of London” - Marshland Publications, London, 1948

Jacob Spon, “Recherches curieuses d’antiquité” - T. Amaulry, Lyon, France 1683

Joseph Strut, “Sports and Pastimes of the People of England” - London, 1793

Henry Thétard, “Coulisses et secrets” - Plon, Paris, 1934

Raymond Toole-Stott, “Circus and Allied Arts” - Derby, 1964

R.W. Vail, “Random Notes” - American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass., USA, 1933

Wilson, “Wonderful! Wonderful! Wonderful!!! The Life and Extraordinary Career of Blondin, the Ascentionist” - C. Elliot, London, 1869

Wallace Collection, London

John Dewe-Matthews

Roger-Viollet

The British Museum

Hertzberg Circus Collection, San Antonio Public Library, Texas

Hugo Williams

Jacques Pavslovski

Victoris and Albert Museum

Murphy Williams

Rayner-Canham

Harold E Edgerton, copyright National Geographic Society

Roger Shaw

Mary Evans Picture Library

Peter Stark

Jean-Louis Blondeau

Hulton Picture Libray

Times Newspapers Ltd

from ’Chinese Acrobats’, Foreign Languages Press, Peking 1974

Claude Champinot, France-Soir

J. Gourmelin

Sunday Telegraph

Mike Goldwater

Andrew Tweedie

Adam Sedgwick

Daily Sketch

David Dyas

Vic de Lucia, New York Post

Michel Jacques

Blondin and Madam Blondin: The British Library

The author at Stratford East: Roger Shaw

Madame Saqui: Bibliotheque Nationale

Horses and tightropes: Bibliotheque Nationale

Tenture des Grotesques: Photographie Giraudon

French Handbill (1810): Bibliotheque Nationale

Madame Romanini and 18th-century French Handbill: Bibliotheque Nationale

La danseuse de cord by Henry de Toulouse-Lautrec: National Museum, Stockholm

the author in ’Jubilee’: Jean-Marc Prouveur